08/01/2025 12:02:53 PM

Risking Life for Art

By Robin Jacobson

The iconic World War II film, The Train, asks whether it is moral to risk human lives to save art. A French Resistance leader initially refuses to direct his men to prevent a train of looted art from reaching Germany. “I won't waste lives on paintings," he tells the art curator who seeks the Resistance’s help.

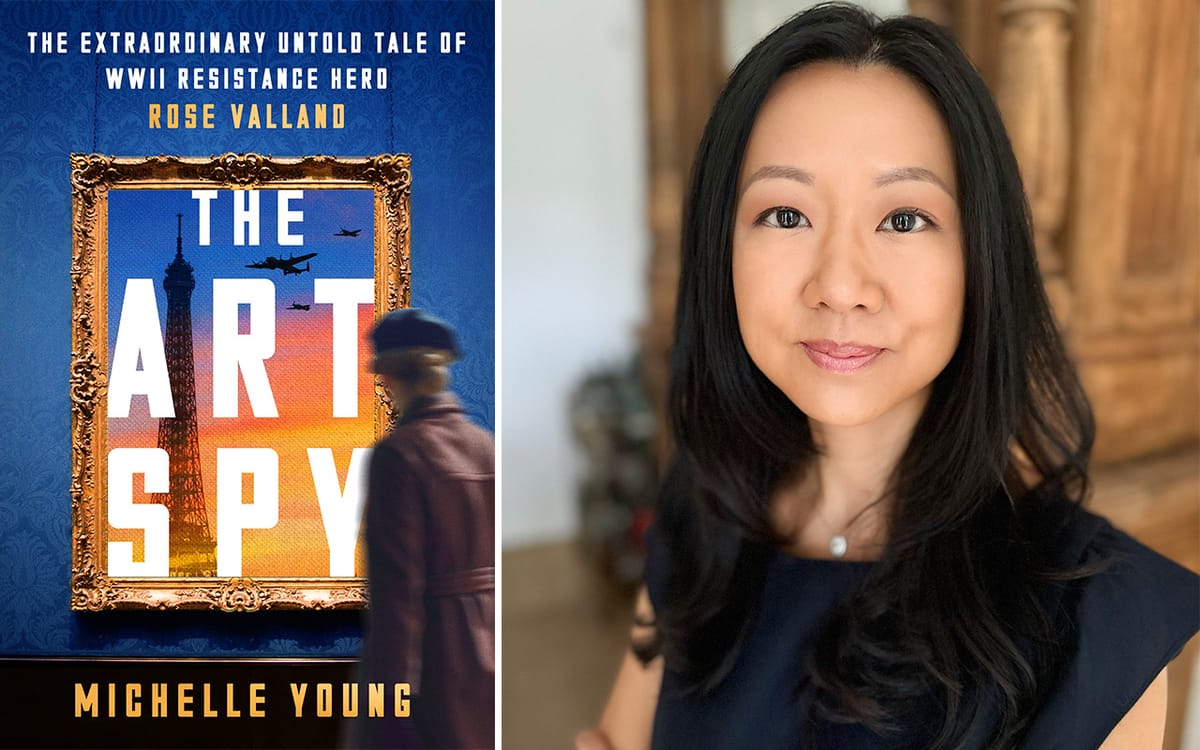

The Train is loosely based on the memoir of Rose Valland, a French art curator who valued art so highly that she risked her life daily during World War II to protect it. Beyond pressing the Resistance to sabotage the art train, she embedded herself within a German art headquarters to secretly track the artworks the Germans looted from Jewish art dealers and other collectors. Her heroic story is thrillingly recounted in a new work of nonfiction, The Art Spy: The Extraordinary Untold Tale of WWII Resistance Hero Rose Valland by Michelle Young.

Humble Beginnings

Born in a small town near Lyon, the daughter of a blacksmith, Rose Valland (1898-1980) loved art from an early age. Despite her humble background, she earned multiple degrees and diplomas in art and art history from the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the Sorbonne, and the École du Louvre, a training ground for future curators, museum administrators, and art historians.

Notwithstanding these impressive academic credentials, the only job Rose could obtain, as a woman in the French art world in 1932, was as an unpaid secretary at the Jeu de Paume, a new museum of international modern art in Paris. She supported herself with side gigs teaching art history, writing about art for newspapers, and brokering art sales. After seven long years, she finally received a museum salary.

Wartime at the Jeu de Paume

When the Germans occupied Paris in 1940, they made the Jeu de Paume their clearing house for processing the art they plundered in France, mostly from Jews. Since she was already working in the museum, Rose was able to present herself to the Germans as a lowly but useful functionary who could continue to oversee the building’s maintenance. They didn’t know that she understood German, had a photographic memory, and was one of France’s most knowledgeable art experts.

A small woman with round spectacles, Rose was often overlooked and underestimated. Her ability to appear unimportant, together with fierce intelligence and determination, enabled her to be a highly successful spy. She eavesdropped, smuggled photographic negatives and German documents out of the museum, and kept copious notes.

Hermann Göring, second-in-command to Hitler, visited the Jeu de Paume many times to choose artwork for his personal collection, utterly unaware that Rose recorded his thefts. Other Germans, however, did become suspicious of Rose, accusing her of aiding the Resistance. Remarkably, on each occasion, she was able to allay her accusers’ suspicions and return to work.

As the Allies approached Paris in August 1944, a German officer sought to send a final trainload of 1000 plundered paintings out of France. Thanks to Rose’s spy work and the skillful sabotage of French railway workers, dramatized in The Train, this shipment was repeatedly delayed until the Free French Forces were able to liberate the train. Rose later wrote that one of her “greatest joys” was to “see all these paintings freed at last, found again by my country.”

Rose’s meticulous records enabled Allied forces to locate hundreds of thousands of stolen artworks Germans had stashed in an Austrian salt mine, German castles, and elsewhere. She personally led a team credited with the restitution of more than 61,000 works of art. Art Spy offers a rich portrait of this World War II hero and valiant defender of cultural heritage.